Imagery captures impressions from the cross-country journey the Vancouver artist undertook after spouse Catherine White Holman’s tragic floatplane death

BY JANET SMITH, STIR VANCOUVER

Pas-à-pas; not intent on arriving is at the SUM Gallery until June 2,, 12 to 6 pm Tuesdays to Saturdays

A PINK SILK flower sits on wet asphalt, pressed against the rough, black surface.

Titled Day 16, the image was taken as Vancouver artist SD Holman was just over two weeks into a cross-country walk, focused on putting one foot in front of the other, overcome with grief. The pilgrimage followed the 2010 death of their spouse, pioneering social worker and Three Bridges Clinic founder Catherine White-Holman, in a floatplane crash off Saturna Island.

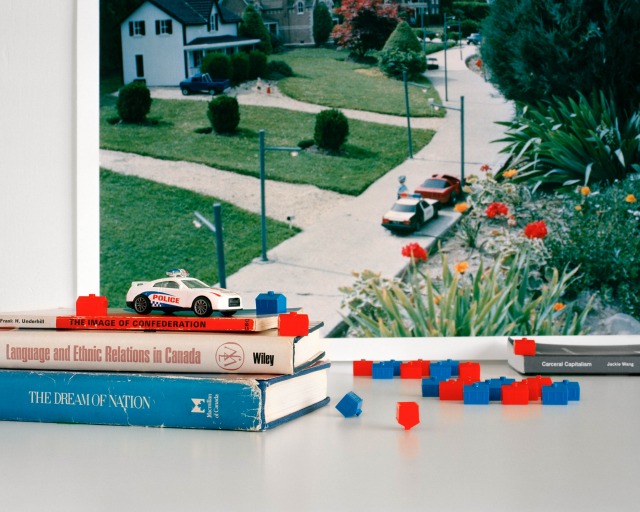

Armed only with a small Canon G11, Holman documented that journey not with pictures of epic Canadian landscapes, but instead with the kind of imagery you see when you put your head down and go: ragged grass, cracked pavement, dead birds, discarded pop cans, flattened bottle caps, and empty masses of gravelly road.

Over three months and 2,700 kilometres, SD Holman took 8,000 images—and now, for the first time, almost 13 years later, they are on exhibit—in Pas-à-pas; not intent on arriving at the SUM Gallery.

“My wife died,” the founding artistic director emeritus of the Queer Arts Festival and its SUM Gallery tells Stir over the phone. “It doesn’t look like it from the outside, but I feel like I’ve been living a half life. And you know, I’ve learned to build a garden around that black hole. But that black hole is always there. ‘Crazy with grief’ is not a metaphor. It is the actual, literal truth. Who would walk across Canada starting April 1?

“All of my friends and family just really didn’t want me to go,” they continue. “I don’t know whether I was going to die; I didn’t care. I was going to find, you know, life out there. I just needed to walk out my door and keep walking. And I do hate walking. I like walking better now, surprisingly, but I really wrecked my knees doing this. I just wanted to walk, so my state of mind was not good. It was yeah, it was really jumbled. I just needed to take a little walk. And I think it was also that I needed to get away.”

Friends helped Holman bring the work to exhibition—including artist Paul Wong, who encouraged Holman to create the exhibit; SUM gallery curator Mark Takeshi McGregor; writer Persimmon Blackbridge, who has worked with words from Holman’s travel journal; and pianist Rachel Kiyo Iwaasa, who brought Bach’s Goldberg Variations to Holman—its looping structures now echoing through the space and acting as an organizing principle for Pas-a-pas.

Walking through the installation-exhibit is a meditative experience. Fittingly, the photographs, each titled after a numbered day during the trip, sit low to the ground. They’re arranged along a curtained pathway, like a kind of contemplative labyrinth. Elsewhere, a grand piano sits empty, and slightly obscured, behind gauzy curtains—suggesting an aching absence, as the Goldberg Variations plays through speakers.

“I really wanted to make it a journey that people could take on their own,” Holman stresses, “because we will all grieve, right? And it’s such a universal thing, but we do it alone. And we don’t like to talk about it…..People ask me, ‘Well, what is that?’ And I’m like, ‘Well, what do you think? What do you see?’”

The entry and exit of the pathway consist of diaphanous white curtains, printed with words from Holman’s travel diary—many of them blacked out—and the unmistakable image of floatplane wreckage, the only direct allusion to the tragedy in the show.

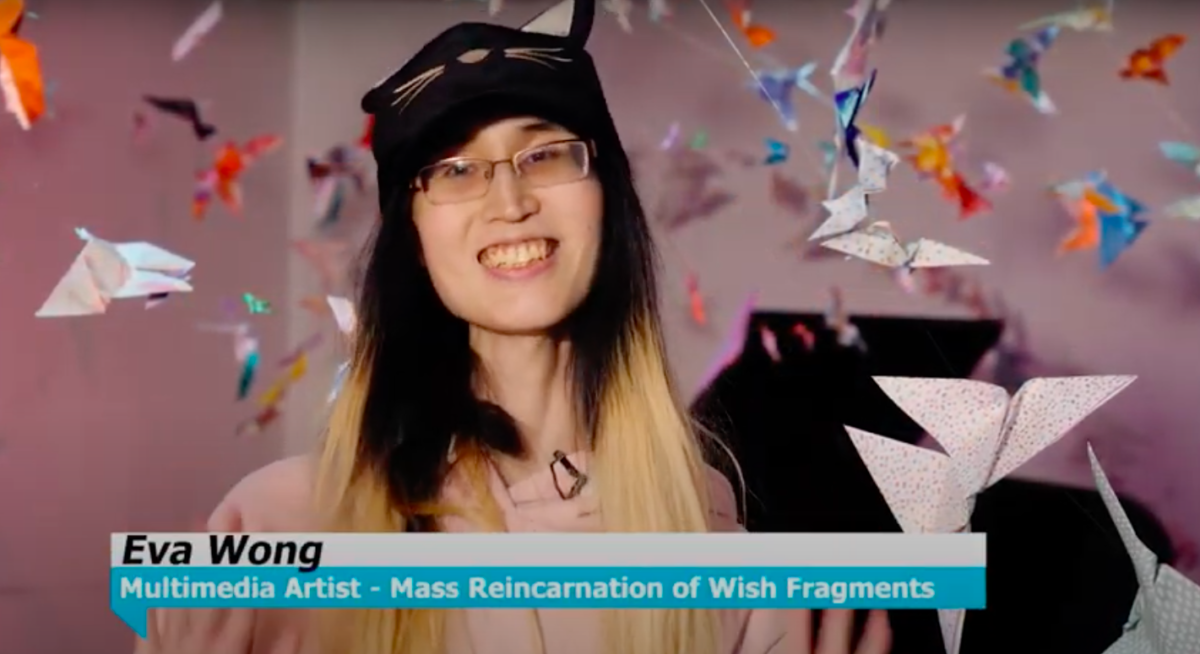

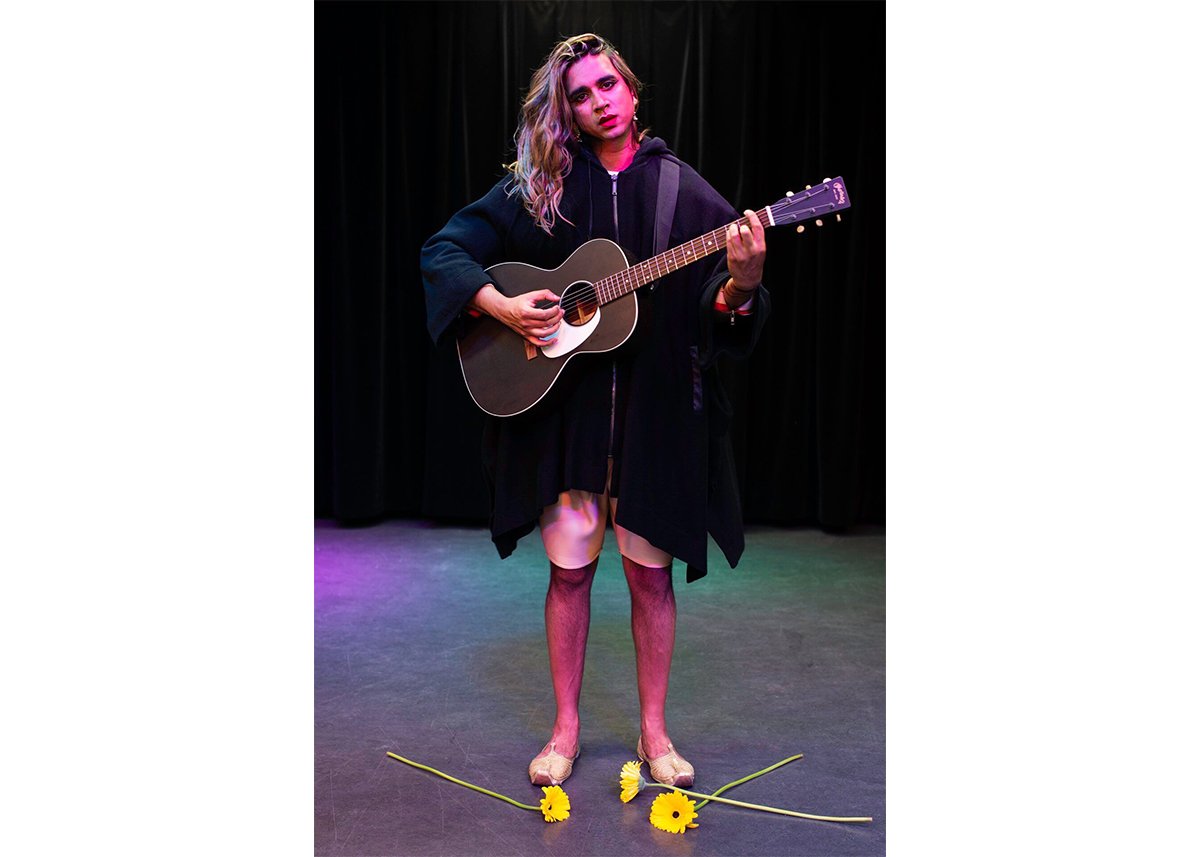

The photographic images themselves juxtapose beauty and harshness; in one, a perfectly preserved dead mouse sits amid roadside rubble; another finds a beautiful speckled bird wing on the pavement. Holman mixes up the printing, with some in colour and some fully desaturated; they call the black-and-white shots the “minor variations”, referring back to Bach’s piece. Though the photos here are impressionistic and sometimes abstracted, Holman is actually best known as a portrait artist, whose photographic series “BUTCH: Not like the other girls” captured the diversity of “female masculinity”. Starting as a transit-shelter public-art project in 2013, it went on to tour North America and became a book.

“I don’t really believe in, like, this perfect moment, but in the many imperfections that make up our messy lives and our messy selves,” reflects the artist. The Emily Carr University of Art and Design grad connects the dots across their photographic practice: “We’re not one thing; there is this dissonance. I think, in everyone, there’s a lot of grey….There’s a terrible beauty in that walk, and taking those pictures and making art out of it.”

One of the most poignant aspects of Pas-à-pas is that it offers little arc or resolution; as the show’s subtitle suggests, it’s “not intent on arriving”. In fact, Holman’s process with the work from their cross-country journey is unfinished as well. They are gathering pieces for future iterations, including one that will draw from Holman’s extensive videos taken during the cross-country pilgrimage. (Called Walk for Love, it raised money for the Catherine White-Holman Memorial Legacy Fund to help LGBTQ2SIA+ people living in poverty, as well as queer women in art .)

“People really want you to move on,” Holman reflects. “And I think that comes from a loving place; people want you to be okay. And there’s a lot of pressure about that. But I think that leaves people feeling really lonely and isolated and you don’t move on. Again, you find you can eventually build a garden around that. But it’s always there.

“We don’t get healed—you just get better at dealing with it,” they add. “And, you know, you realize there’s other great people in the world and other things to do, but it’s always there. And that’s an honouring: grief is love. Right? It is the relationship that you have with that person. That grief is love. So letting go of that, I think, lets go of that love. That love is always there.”